3, 4-methylene-dioxy-meth-amphetamine was initially an off-label prescription available from your local psychiatrist from the late 70’s to the early 80’s. Known simply as ‘X’ or ‘E’, today MDMA—better known as ecstasy—is the second most widely abused recreational drug in western Europe and increasingly popular in the US and Australia. Not all “ecstasy” tablets contain MDMA, although epidemiological evidence indicates that major side effects from ecstasy intoxication are rare and idiosyncratic. But ask any epidemiologist: if enough people use something often enough, then rare and idiosyncratic become ‘well-described’.

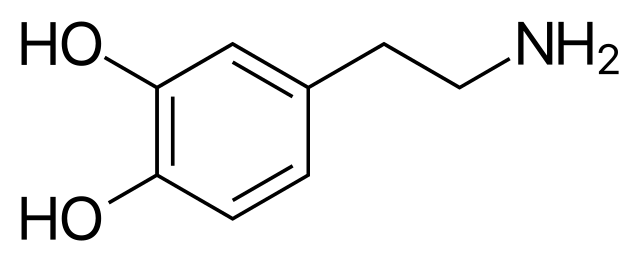

High-dose MDMA administration in animals causes a depletion of brain serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, or 5-HT) levels. These experiments initially induced a rapid and potent release of catecholamines—serotonin, dopamine (DA), and norepinephrine (NE)—from brain nerve endings. The overall balance of these central neurotransmitters accounts for the unique characteristics of MDMA. By contrast, amphetamine-like effects are mediated predominantly through nerve-terminal release of dopamine (DA) in the brain.

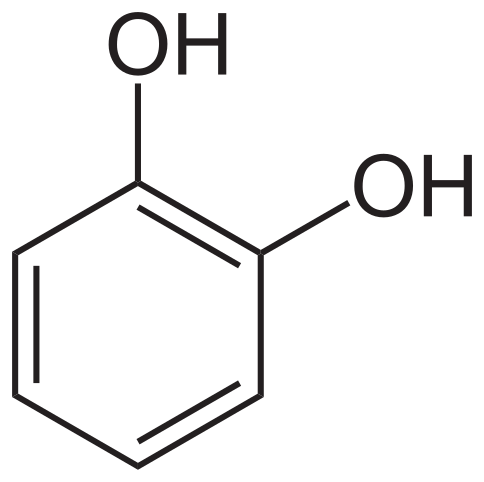

|

| Catechol [Wikimedia Commons] |

These same animal studies confirm that MDMA, in high acute doses, is specifically neurotoxic to brain serotonergic nerves. This nerve degeneration—identified chemically and confirmed in autopsy specimens—lasts for months in rats and years in primates, while other transmitters, in general, appear unaffected. But lower-dose long-term use appears to selectively target the dopaminergic nerves. Fenfluramine (or 3-trifluoromethyl-N-ethylamphetamine) is an appetite suppressant (Pondimin, Ponderax, Adifax) that has since been withdrawn from the US market. Fenfluramine selectively releases only serotonin.

|

| Dopamine (ethylamine) is a catecholamine [Wikimedia Commons] |

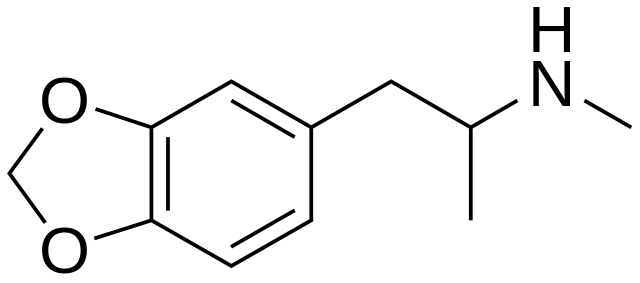

Theoretically then, the effect of ecstasy should be akin to taking both amphetamine and fenfluramine together, as well as the (observed) ability of MDMA to model the locomotor activation induced by the interaction of dopamine and serotonin. MDMA is a potent ‘releaser’ (actually, a “re-uptake inhibitor”) of serotonin (5-HT), dopamine (DA), and norepinephrine (NE). That is, MDMA use makes these neurotransmitters more abundant (and consequently have a greater effect) around the nerve endings in the brain.

Other catecholamines include adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine). Related to the catecholamines, and metabolised in-vivo by the same mechanisms, are both MDMA and serotonin:

|

| 2D structure of MDMA [Wikimedia Commons] |

|

||

| 5-hydroxytryptamine or Serotonin [Wikimedia Commons]

The effects for which MDMA has gained renown as a ‘party drug’ include euphoria, a feeling of well-being and enhanced mood, psycho-stimulation, increased energy and hyperactivity, extroversion and a sense of closeness to others, sociability, mild perceptual disturbances, changed perception of colours and sounds, derealisation without hallucinations, and reflex cardiovascular effects of raised blood pressure and heart rate, and dilated pupils. Peak MDMA effect occurs one to two hours after a dose, without any secondary peak after typical recreational doses (ranging from 46 to 150 mg). In these people, the highest heart rate achieved was 132 beats per minute (normal 60-100) and the highest blood pressure recorded 171/102 mm Hg (normal 120-130/80). One of the main serious side effects of Ecstasy use is the Serotonin Syndrome of increased muscle rigidity, heightened reflexes, and a dose-dependent rise in body temperature. This effect is exacerbated by high ambient temperatures and the ingestion of other metabolic stimulants or diuretics—such as caffeine, energy drinks, and alcohol. A full-blown serotonin syndrome can, and does, kill.

|

Subtle intellectual (particularly memory) deficits are the most common finding with heavy ecstasy use. Studies in humans suffer from all manner of bias, not least of which is widespread multiple drug use (alcohol, cannabis, amphetamines, cocaine) in participants, which confound any results. But the evidence suggests a residual alteration of serotonergic transmission in MDMA users. While partial resolution may occur after long-term abstinence, sequelae can persist. The manifestations of ecstasy-induced serotonin injury may only become apparent with time or under periods of stress, so that some people with no obvious problem could develop complications in the longer-term.

In a 1992 Lancet article looking at toxicity and deaths related to MDMA use, seven deaths were attributed to uncontrolled high body temperatures, convulsions, clotting problems, massive muscle breakdown, and kidney failure. A further seven cases of liver toxicity were discovered. The authors also described five cases of road traffic accidents, in which MDMA was identified. Other potential serious complications are a high lactic acid, severe hypertension, and cardiac arrhythmias (heart rhythm irregularities).

MDEA and MDA are two similar drugs that are also commonly consumed recreationally (often inadvertently), with MDMA equally or slightly less toxic than MDA (3, 4-methylene-dioxy-amphetamine). All three are psychedelic amphetamines with fairly similar effects, although connoisseurs invariably prefer MDMA because of its empathic effects. MDA lasts twice as long (8-12 hours) and has a rather more amphetamine-like effect. MDEA (sometimes sold as “Eve”), lasts a rather shorter time (3-5 hours) than MDMA (4-6 hours) and is nearer to MDMA in effect, but still lacks its communicative qualities.

Ecstasy tablets may contain any or all of the following:

- MDA (3, 4 methylene-dioxy-amphetamine)

- MDEA (3, 4 methylene-dioxy-ethyl-amphetamine) also known as MDE or Eve

- mixtures of LSD and amphetamine or caffeine

- up to 10% may be fakes with no effect, or worse still, with potentially harmful drugs or excipients

The MDMA effect wears off after a few successive days’ use of ecstasy (or its analogues), a phenomenon known as tolerance. However, no cross-tolerance is seen between MDA and MDMA: someone who has taken so much MDMA that it has no more effect on them can still ‘get off’ on MDA, and vice versa.

Nonetheless, subsequent exposures would create less and less of that ‘loving feeling’ and more and more ‘speediness’, for up until five days wherein the feeling of affinity would all but cease. Abstinence for a time would allow the respective neurotransmitter system to refresh, at which time the ‘good’ effect would be experienced on subsequent use. Perhaps a week without MDMA is long enough for its effect to be reset, although for the full effect abstinence may have to occur for up to six weeks. Regardless, it may never be as ‘good’ as the initial experience.

In a Sydney observation, ecstasy reportedly shared properties of both amphetamines and hallucinogens in the nature of its side-effects and residual effects, and was no more severe than either of those two drugs. Tolerance was reported to develop to its positive effects, while the negative effects increased with use. It has been suggested that tolerance is generally a noticeable phenomenon by those who take more than one ‘E’ a week.

Over 15.3 million estimated drug-use disorders were reported worldwide in 2009 according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). This includes but is not limited to ‘Drug Dependence’, which is specifically defined by the WHO as “a cluster of cognitive, behavioural and physiologic symptoms that indicate a person has impaired control of psychoactive substance use and continues use of the substance despite adverse consequences”.

References:

Baumann MH, Wang X, Rothman RB. 3, 4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) neurotoxicity in rats: a reappraisal of past and present findings. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2007 Jan; 189 (4): 407-24. Epub 2006 Mar 16.

Green AR, Mechan AO, Elliott JM, O’Shea E, Colado MI. The pharmacology and clinical pharmacology of 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”). Pharmacol Rev. 2003 Sep; 55 (3): 463-508. Epub 2003 Jul 17.

Bankson MG, Cunningham KA. 3, 4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) as a unique model of serotonin receptor function and serotonin-dopamine interactions. J Pharmacol Exp. Ther. 2001 Jun; 297 (3): 846-52.

de la Torre R, Farré M, Roset PN, Pizarro N, Abanades S, Segura M, Segura J, Camí J. Human pharmacology of MDMA: pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and disposition. Ther Drug Monit. 2004 Apr; 26 (2): 137-44.

Kolbrich EA, Goodwin RS, Gorelick DA, Hayes RJ, Stein EA, Huestis MA. Physiological and subjective responses to controlled oral 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine administration. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008 Aug; 28 (4): 432-40.

Parrott AC. MDMA in humans: factors which affect the neuropsychobiological profiles of recreational ecstasy users, the integrative role of bioenergetic stress. J Psychopharmacol. 2006 Mar; 20 (2): 147-63.

Thomasius R, Zapletalova P, Petersen K, Buchert R, Andresen B, Wartberg L, Nebeling B, Schmoldt A. Mood, cognition and serotonin transporter availability in current and former ecstasy (MDMA) users: the longitudinal perspective. J Psychopharmacol. 2006 Mar; 20 (2): 211-25.

Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E, Daumann J. The confounding problem of polydrug use in recreational ecstasy/MDMA users: a brief overview. J Psychopharmacol. 2006 Mar; 20 (2): 188-93.

Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E, Daumann J. Neurotoxicity of methylenedioxyamphetamines (MDMA). Addiction. 2006 Mar; 101 (3): 348-61.

Adverse reactions with 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA; ‘ecstasy’). Drug Saf. 1996 Aug; 15 (2): 107-15.

Altered states: the clinical effects of Ecstasy. Pharmacol Ther. 2003. Pharmacol Ther. 2003 Apr; 98 (1): 35-58.

Henry JA, Jeffreys KJ, Dawling S. Toxicity and deaths from 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamp. Lancet. 1992 Aug 15; 340 (8816): 384-7.

Davis WM, Hatoum HT, Waters IW. Toxicity of MDA (3, 4-methylenedioxyamphetamine) considered for relevance to hazards of MDMA (Ecstasy) abuse. Alcohol Drug Res. 1987; 7 (3): 123-34.

Henry JA, Jeffreys KJ, Dawling S. Toxicity and deaths from 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamp (“ecstasy”). Lancet. 1992 Aug 15; 340 (8816): 384-7.

Solowij N, Hall W, Lee N. Recreational MDMA use in Sydney: a profile of ‘Ecstasy’ users and their experiences with the drug. NADIA SOLOWIJ. 2006; British Journal of Addiction. Volume 87 Issue 8, Pages 1161 – 1172 (Published Online: 24 Jan 2006. 1992 Society for the Study of Addiction to Alcohol and Other Drugs).

The chance of getting a good E in Britain (1995) – http://www.ecstasy.org/testing/purity.html

Information Source for Drug Dependency – http://www.isdd.co.uk/