Tissue Response

Inflammation

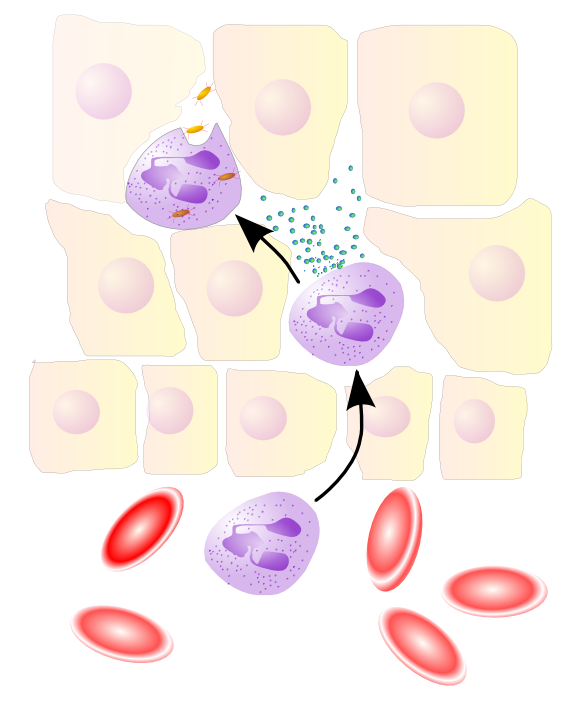

Acute Inflammatory Response: an innate immune response is immediately triggered with cytokines, chemotaxis, and neutrophilia.

Granulation Tissue: an early, organising inflammatory response that follows on from the acute inflammatory response.

Chronic Inflammation: a prolonged inflammatory episode recruiting adaptive processes for healing.

Ulceration: epithelial erosion

Thrombosis: haemostatic plug and thrombosis.

Oncogenesis: genetic mutability

Cellular Adaptation to Stress

Cells have a stereotypical way of responding to insult. Cells do so either by:

- hypertrophy: increase in cell and organ size (often in response to increased workload)

- hyperplasia: increased cell numbers; in tissues whose cells are able to divide or contain abundant tissue stem cells

- atrophy: decreased cell and organ size, as a result of decreased nutrient supply or disuse

- metaplasia: change in phenotype of differentiated cells, often in response to chronic irritation, that makes cells better able to withstand the stress; usually induced by altered differentiation pathway of tissue stem cells

A more acute and more severe insult will often lead to cell death, or necrosis. A more regular, programmed cellular death, apoptosis, is more commonly a physiological process of eliminating unwanted cells but can be pathologic after some forms of cell injury, especially cell injury, DNA and protein damage.

Apoptosis is the regulated mechanism of cell death that serves to eliminate unwanted and irreparably damaged

cells, with the least possible host reaction and impairment to function. Apoptosis is characterized by enzymatic degradation of proteins and DNA, initiated by caspases; and by recognition and removal of dead cells by phagocytes. Apoptosis is initiated through two major pathways:

- Mitochondrial (intrinsic) pathway: triggered by loss of survival signals, DNA damage and accumulation of misfolded proteins

- Death receptor (extrinsic) pathway: responsible for elimination of self-reactive lymphocytes and damage by cytotoxic T lymphocytes; is initiated by engagement of death receptors (members of the TNF receptor family)

Necrosis is characterized by changes in the cytoplasm and nuclei of the injured cells:

- Cytoplasmic changes. Necrotic cells show increased eosinophilia

- Nuclear changes. Nuclear changes assume one of three patterns, all due to breakdown of

DNA and chromatin — karyolysis (fading of basophilic chromatin); pyknosis (nuclear shrinking with basophilic concentration); karyorrhaxis (a pyknotic nucleus now undergoing fragmentation).

Necrotic cells may persist for some time or may be digested by enzymes and disappear, giving certain distinctive types of necrosis morphology:

- coagulative necrosis: underlying tissue architecture preserved (at least for several days)

- liquefactive necrosis: focal bacterial or, occasionally, fungal infections, because microbes stimulate the accumulation of inflammatory cells and the enzymes of leukocytes digest (“liquefy”) the tissue

- caseous necrosis: a “cheese-like” friable yellow-white appearance to the necrosis most often seen in foci of tuberculous infection

- fat necrosis: focal areas of fat destruction, typically resulting from release of activated pancreatic lipases into the substance of the pancreas and the peritoneal cavity; released fatty acids combine with calcium to produce grossly visible chalky white areas (fat saponification); histologically, the foci of necrosis contain shadowy outlines of necrotic fat cells with basophilic calcium deposits, surrounded by an inflammatory reaction

- fibrinoid necrosis: special form of necrosis, visible by light microscopy, usually in immune reactions in which immune complexes (antigens and antibodies) are deposited in the walls of arteries; the deposited immune complexes, together with fibrin that has leaked out of vessels, produce a bright pink and amorphous appearance on H&E preparations called fibrinoid

The fundamental basis of cell injury may involve any or all of the following:

- ATP depletion

- mitochondrial damage

- calcium influx

- accumulation of reactive oxygen species

- increased cell-membrane permeability

- accumulation of damaged DNA and misfolded proteins

- e.g. Tay-Sachs disease, Alzheimer Disease

Abnormal Intracellular Depositions and Calcifications:

Abnormal deposits of materials in cells and tissues are the result of excessive intake or defective transport or catabolism. Materials deposited include lipids (fatty change, cholesterol deposition), proteins, glycogen (glycogen storage diseases), pigments, and pathologic calcifications, either dystrophic calcification, at sites of cell injury or necrosis, or metastatic calcification, the deposition of calcium in otherwise normal tissues because of a hypercalcaemia.

Kumar, Vinay, Abbas, Abul K., Aster, Jon. Robbins Basic Pathology. 9th Edn. Elsevier, Saunders, 2013.